As you know if you’ve been reading my blog, I recently went on a solo-play excursion, learning the amazing game Dungeon Crawl Classics by Goodman Games and playing through their starter, level-0 “Funnel” The Portal Under the Stars. You can find the beginning of this excursion here, and at the end of each post is a link to the next installment. All in all, there are seven posts in the series.

Now that the story is done, I thought it might be fun to strip out all the gameplay sidebars and see how it works as an actual story. Importantly, as I wrote the previous installments, I had no idea what would happen and now I do. This insight gives me an opportunity as a fiction writer to go back through the entire emergent narrative—which was done with dice rolls and in a serial format—and foreshadow later happenings, delete irrelevant parts, focus on key characters, and just generally make it a more cohesive, self-contained, story. Oh, and fix tons of typos.

Below is that “cleaned up” text, which is the kind of thing that might start off a longer fiction series. If you’ve been following along on the solo-play adventure, you can experience a retelling here that is akin to a traveling bard, sharing a tale that you know actually happened somewhat differently. If you have zero interest in role-playing games but like fantasy fiction, well then here is a short piece of fiction into another world, and a group of characters I might continue to explore. Either way, ENJOY!

0.

Bert Teahill lay under a pile of threadbare blankets, shivering and groaning. He was little more than sun-shriveled skin stretched over bones, his gray hair plastered to his skull with sweat. The cramped room–barely large enough for the small bed, a footlocker, and the five figures crowding round–smelled strongly of urine.

The old man coughed weakly. “Is everyone here then?” he asked in a voice dry as summer leaves.

“We’re all here, Bert,” sniffed Councilman Wywood, nodding. He glanced at the other three town council members, each doing their best to not be there. Wywood was the oldest and most tenured council member and often spoke first. Councilmen Wayford and Seford weren’t much younger but still deferred to him. Indeed, the three men had held their positions so long that they seemed to share more unsaid with their glances than spoken aloud. For example, right then Seford, small eyes in a round face with hanging jowls, looked to Wywood imploringly as if to say, When can we leave and get back to our brandy?

The fourth council member, Councilwoman Leda Astford, was the newest member and everything the others were not. Young, brave, and earnest, she interrupted the silent glances from the other three.

“What is it you wanted to tell us, Bert? We’ve assembled the full town council and your grandson, just as you asked,” she said, bending down to lay a hand on Bert’s shoulder. Councilman Wywood, for his part, pursed his lips and sniffed derisively. The other two old men nodded at his annoyance, silently agreeing, Who does she think she is, taking charge?

Bert Teahill whimpered and stirred feebly beneath his covers. For a moment he stilled, and the room grew silent. Then the old man sucked in a breath and opened his eyes wide, searching around the room. He coughed.

“Good, good. Listen to me, all of you. The star… the stars have come back as when I was a boy.”

“What are you saying, Bert?” Wywood grumbled. “What is this about stars?”

“Let him speak, please,” Leda intoned. The other three council members traded offended, frowning glances.

“When I was a boy,” Bert continued, wheezing. “Must be fifty winters since. I used to watch the stars, notice how they formed pictures in the sky. Once there was a peculiar star. Called it the Empty Star, a blue, twinkling thing, all on its own with no others around it. As it rose directly overhead, a… a door opened. Shimmering blue, at the old stone mound. Swear to all the gods I saw it! A bright blue door, and on the other side jewels and fine steel spears aplenty.”

“What is he suggesting?” Councilman Wayford scoffed at his brethren. He was stooped with age, and his voice was high and wheedling, as if he were always whining. “We’re all here for a child’s fable?”

“A portal!” Bert said, his voice suddenly strong. A liver-spotted hand emerged from the blankets and gripped Leda’s wrist. He looked up at her imploringly. “All my life I held this secret, wishing I’d gone in. Could have changed my fortune, maybe my whole family’s fortunes. Maybe the whole town’s! And every night since I’ve watched the stars. The pictures in the sky all changed. The Empty Star never came back.

“But now it’s back, you hear me? The Empty Star is rising! Tomorrow night, sure as my grave, it’ll happen! I feel it in my very soul, you hear me? Tomorrow night is the night! Someone has to go to the old stone mound to see the portal. Go in, this time. Change Graymoor’s fortunes! There’s treasure there, and glory. Don’t let it pass by this time, please. Don’t live a life of regret like an old, dying farmer. Please. Please…” And just as suddenly as his old, vital self had returned, Bert Teahill deflated and lay panting.

The three aged councilmen said nothing, eyes darting furtively between them in silent discussion. Leda Astford, meanwhile, patted the farmer’s shoulder gently.

“Okay, Bert,” she said. “We hear you. We’ll go to the old stone mound tomorrow night. If there’s a portal, we’ll get those jewels and spears.”

“Take– take Gyles,” Bert whispered and almost imperceptibly nodded.

With a rustle of cloth and creaking floorboards, the four town council members turned to look at the boy. Little Gyles Teahill was Bert’s grandson, who townsfolk said was strong as a man at ten years of age. He had taken over running the Teahill farm with his father’s recent leg injury. Little Gyles looked up at them all with a mix of wide-eyed surprise from the attention and an iron-like determination.

Councilman Wywood snorted derisively and turned his back on the boy. Wayford and Seford followed suit. The three shuffled out of the room, muttering about “waste of time” and “fool’s errand” and “preposterous” and “let’s go have some brandy.”

Leda Astford, meanwhile, met the boy’s eyes. She smiled, conjuring a confused grin from the boy. As the others left, Leda gently squeezed Bert’s thin shoulder and nodded. “I’ll go myself tomorrow night, Bert. And I’ll take Little Gyles and keep him safe, don’t you worry. We’ll see this door of yours. And if it’s there, well, sure as anything we’ll go in.”

Bert Teahill lay still beneath his blankets, eyes closed and barely breathing. Had the man heard her words?

They would never know.

I.

Councilwoman Leda Astford’s breath steamed in the cold night air. Spring had come to Graymoor, but Winter still had its grip on the dark hours. She shivered beneath her traveling cloak, pulling it tighter. She was a healthy woman in the prime of her life but had always suffered in the cold. Her hands and feet especially.

A rumor as big as this one had spread, and a large pack of residents had volunteered to wander into the darkness in search of Old Bert Teahill’s flight of fancy. Puffs of breath dotted the shadows as the dozen of them waited. It was a clear night and the path to the old stone mound was well-known, so none had felt the need to light a torch.

“How long are we going to stay out here before we decide the old fool is crazy?” complained Egerth Mayhurst. He was Graymoor’s jeweler, a shrewd and unpleasant man of middle years, thin and bald, with a carefully sculpted beard along his jawline. Though no one asked him, it seemed he was here to lay claim to any gemstones they found, if a magic portal did exist. Or perhaps he may have been sent here to report back to the other council members.

“Calm yourself, Egerth,” a deep, resonant voice intoned. It was Bern Erswood, the town’s herbalist and likely the most well-liked of the group. Bern’s remedies rarely did what he claimed, but the barrel-chested, bearded man made you feel good about taking them all the same. “That blue star that Leda called the Empty Star… It’s still climbing in the sky, and it’ll soon be directly over the old stones. I’m not saying anything will happen then, mind you, but I reckon we’ll find out soon.”

The others mumbled their assent and Egerth Mayhurst snapped his jaw shut, arms folded. Leda looked down on Little Gyles, who stood near her with a pitchfork held like he was defending a castle from invasion. The boy had stayed at her side the entire trek. Leda smiled and gripped his firm, muscled shoulder.

“You hear that? Shouldn’t be long now,” she said reassuringly. The boy pursed his lips and nodded.

On her other side stood a tall, willowy figure. Finasaer Doladris was the only elf anyone in Graymoor had ever met, and his long, pointed ears and long, fine hair made for a distinctive profile even in the darkness. His robes seemed to shimmer in the starlight.

“What do you think, Mister Doladris?” Leda asked. “Will a portal appear?”

“Mm,” he murmured noncommittally. “Difficult to ascertain, councilwoman. Yet whether folk fable or astrological miracle, it’s a fine entry to my documentation of the local populace. Quite intriguing all the same.”

Leda didn’t reply. The elf had been a genuine curiosity to all of Graymoor since he appeared out of the woodland a year ago claiming to be doing research, but the way he spoke made it difficult to hold a conversation.

The old stone mounds were named such because, amidst a marshy woodland, several large slabs of rock lay against one another randomly like the discarded toys of giants. No other such stones could be found within miles of Graymoor and, against all reason, these immense stones never collected moss, bird nests, or spiders. Indeed, no vegetation of any kind grew near the stones. Naturally, most locals avoided the place, and it was a frequent object of childhood dares. If Bert was indeed making up a story, the old stone mound was the perfect location for it.

Suddenly, where three blocks leaned haphazardly together to form an upright rectangle, a shimmering door of light appeared. One moment the space was empty and then it wasn’t, without a sound. The dozen Graymoor residents gasped.

A handful crowded forward to peer inside. It was not so much a door as the opening of a corridor. Where before there had been a person-sized gap in the stones, there now stretched a long hallway, limned by blue light.

“There’s nothing on the other side!” Veric Cayfield, one of the three halflings present, called out from the shadows. Like the Haffoot siblings who had also joined their party, Veric had migrated to Graymoor from the distant halfling village of Teatown. He had become the town’s haberdasher years ago, because there was nothing Veric loved so much as clothes and sewing. Indeed, he proudly exclaimed to anyone who would listen that the reason he loved Graymoor is because humans allow him the opportunity to use even more fabric for his craft. They were a curious, wide-eyed lot, halflings, so no surprise that they’d come along.

“Sure enough!” Bern the herbalist exclaimed. “I can see you all clearly through the gap on this side. Can you see me?”

“We can’t, Bern,” Leda called out, and it was true. “For us it’s a hallway.”

The sound of a sword being pulled from its scabbard rang out. Mythey Wyebury, known troublemaker, moved forward to the shimmering corridor’s opening. He was a thin man, scruffy, with a long neck and bobbing adam’s apple. “Well?” he said. “So the old man was speaking true. Let’s go find these jewels and magical weapons, eh?”

And then he stepped into the portal.

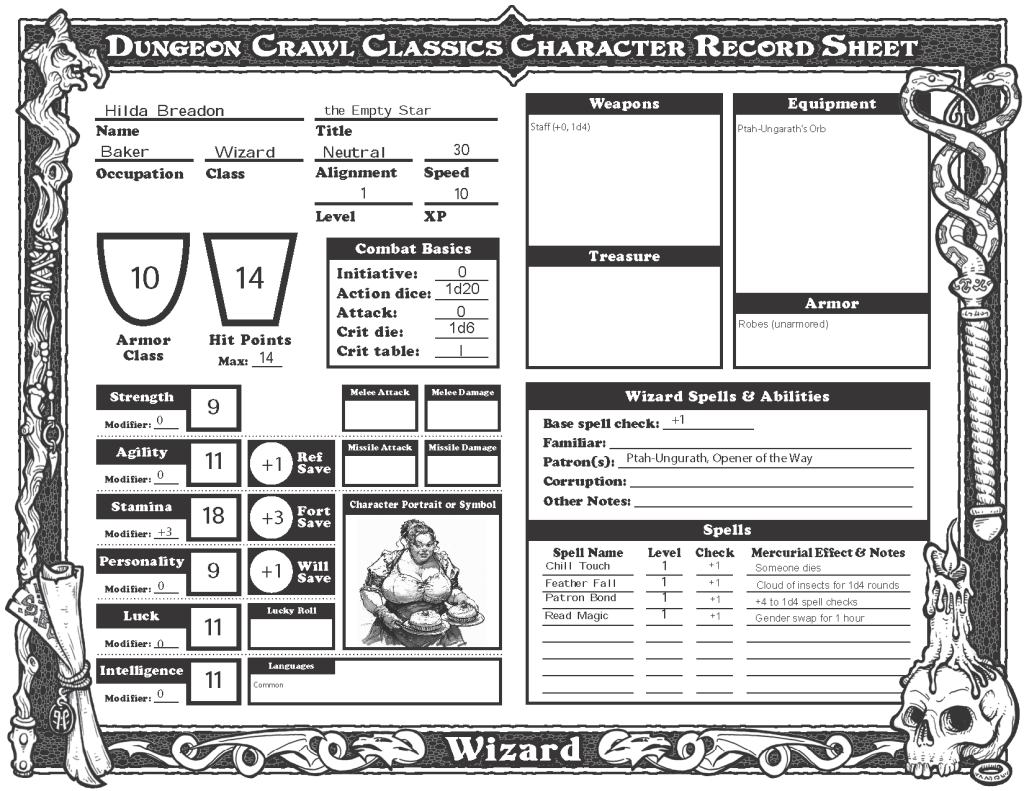

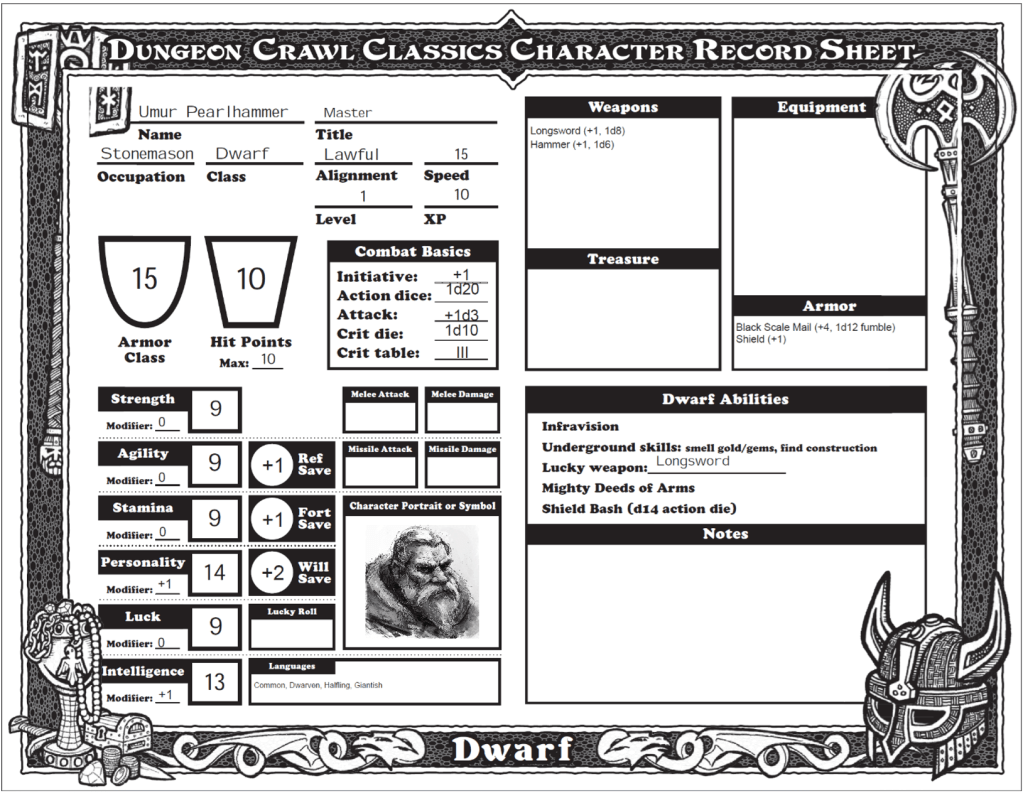

Hesitantly, a small group followed, each clutching the closest thing to a weapon each could find at home. Umur Pearlhammer, the dwarven stonesmith and Graymoor’s most tenured resident, gripped a hammer. Erin Wywood, the councilman’s granddaughter, had a long knife in her shaking hand. Even Hilda Breadon, the town’s baker extraordinaire, gripped a rolling pin in her meaty fist.

The corridor before them ran about twenty feet, all bare walls of the same sort of stone as the old stone mound. It was Umur who pointed out the flagstone floor that ran between the portal opening and a large door. The old dwarf muttered that it spoke of someone crafting this place instead of it simply… being. His words tightened the grips everyone had on their weapons.

“Locked!” Mythey shouted from the front, clearly frustrated. Veric, Bern, and the others who had walked around the stones were now all at the portal’s entrance. With them, the last of the twelve stepped inside.

The door was wooden and banded in iron. Jewels or crystals of some sort were embedded in the wood, creating star-shapes that twinkled in the blue light.

“I think,” Erin Wywood started to say, her voice cracking. She cleared her throat and tried again. “I think we need to wait. Bern said the star wasn’t directly overhead yet.” Most everyone there thought of Erin as the young, earnest minstrel who sang religious tunes in the tavern, or else Councilman Wywood’s favorite spawn. What they didn’t know is that she had a sharp mind and cool head.

“Screw that!” Mythey spat from the front of the group. Before anyone could stop him, he put his hand on the door’s handle and bashed forward with his broad shoulder. The young man with unwashed, stringy hair was an ass and bully, but he was also hulking and easily the strongest of them assembled.

It was a solid blow, but the door held. As Mythey struck it, the jewels on its surface flashed a bright blue that left all of them within the corridor dazzled. For a moment, they all blinked to regain their vision.

“He’s dead!” Hilda the baker shrieked, the first to clear her eyes. “Burned to a crisp! Gods help us!”

Acrid smoke smelling of charred flesh began drifting through the corridor towards the open air. The residents gagged and rushed towards the exit, with several glancing back at the blackened lump that was once Mythey Wybury.

As the now-eleven of them huddled outside, under the night sky, near the shimmering portal entrance, many tried talking at once, some in hysterical, high-pitched tones and others in calm, reassuring ones. The effect was that no one heard a single thing the others were saying, leading to a chaotic babble.

“Enough!” Umur Pearlhammer shouted. At once they all quieted. The dwarf’s weathered face, bushy brows over a bulbous nose, regarded them. “Mythey was a fool and trouble besides, we all knew it. First chance he had to take whatever wealth and steal it, he would have. I donna’ like that he died, mind, but there’s a lesson there for all’a us.”

The others nodded and sniffled and gripped their weapons.

“We gotta take care, now,” the dwarf continued in his gruff, commanding voice. “Think an’ act together, yeah? Miss Wywood has the right of it, methinks. What say you, Bern? The Empty Star still trackin’ overhead?”

The herbalist scanned the sky. “I would say so, yes. Maybe an hour or two and it should be directly overhead.”

Umur nodded once. “Then we wait. Meantime, who can help me haul tha’ fool’s body out so we can bring it back when we’re done and through?”

For a moment, no one said a word. Then Little Gyles Teahill raised his hand. “I can help, Master Stonemason sir.”

Umur nodded again. “Right enough. Come along lad.”

The next hour or two passed slowly. Mythey’s body was badly burned and uncomfortable to see, like he’d been struck by lightning. But he had a short sword in his grip and was the only one of them wearing anything resembling armor. After the trapped door, such things seemed more important than ever. Umur offered to take the sword, since no one else seemed comfortable using it. The leather cuirass, however, would never have fit the stocky dwarf. Indeed, only Bern the herbalist, Egerth the jeweler, and Finasaer the scholar were anywhere near the man’s size. The elf held up his hands helplessly, saying he was not a man of arms. That left the two human men, and, after some discussion, Bern had the least distaste for wearing a dead man’s singed leathers. Several of them managed to pull the items from Mythey’s corpse and help Bern with the straps. Umur swung the sword, away from the group, and grunted in satisfaction as he slid it back into the scabbard that now hung from his hip.

“Something’s happening!” one of the Haffoots, the sister, Ethys, exclaimed, pointing a small finger towards the glowing hallway.

Bern looked skyward, drumming a finger on his now leather-clad belly. “Mm. Looks like it’s directly overhead, sure enough.”

“What is it, Ethys?” Councilwoman Leda asked as the group edged near the stones. It was an unnecessary question. Anyone with a view down the long corridor could see what was happening.

The jewel-encrusted, heavy door swung open.

II.

The Graymoor residents pressed together in the cramped corridor, attention fixed ahead.

Old Bert Teahill had claimed that beyond the magical portal lay “jewels and fine steel spears.” There were gem-like crystals on the now-open door, dotting the wooden surface in star-like patterns. After Mythey’s fate, none were too eager to try prying them from the wood, though.

And spears? Yes, there were certainly spears.

In a rectangular room, perhaps ten feet from the open doorway, straight ahead, was another stout, wooden door banded in iron, no crystals upon its surface. Four armored iron statues, two on each side, flanked that door. Each statue depicted a person–human men and women, judging by the physiques, ears, and roughly carved faces–in enameled, scaled armor holding a black spear, arm cocked back as if ready to throw. All four deadly spear-tips aimed directly at the open doorway.

Bern Erswood, the herbalist, pulled the councilwoman aside forcefully.

“Leda! If those things loose those spears, you’re as dead as Mythey, that’s for sure,” he whispered fiercely, admonishing.

“If it were a trap,” sniffed Egerth Mayhurst, the unpleasant jeweler, panting, flattened himself on the opposite side of the hallway as Leda and Bern. His bald pate gleamed with nervous sweat in the pale blue light. “It would have triggered, yes? Perhaps it was meant for someone who forced the door open before it was unlocked.”

“Well then, by alla’ means,” the dwarf, Umur Pearlhammer, grumbled from behind him. The others, deeper down the corridor, similarly pressed to the sides. “Go on in and try the next door, yeah?”

“Absolutely not!” Egert blanched.

“I’ll- I’ll do it,” stammered Little Gyles, Bert’s grandson. He planted his pitchfork and pushed forward.

“No, son,” Umur and Bern said almost simultaneously, then chuckled at one another.

“Bravest one here is the wee lad,” Umur shook his head. “Step aside, step aside. We’re here. Might as well see what’s behind that next door since we’ve come alla’ this way.”

“I’ll join you, Master Pearlhammer,” Bern smiled, and the two men stepped into the room, shoulder to shoulder. Undaunted, Little Gyles was right on their heels.

Nothing happened. Several of them exhaled loudly at the same time.

Suddenly, with a coordinated, metallic THUNK! and a quick whirring noise, the four statues released their spears in unison. Before the Graymoor residents could gasp, one had buried itself in Umur’s broad shoulder, another had clattered against the wall behind Bern, and a third had sailed through the doorway, narrowly missing Egerth’s leg and skittering across the stone floor amidst the others. The dwarf cried out in pain and stagged just as the jeweler clawed at the wall, backpeddling into the pressed crowd.

“No!” Bern yelled, much to those in the back’s confusion. And then Little Gyles Teahill, the boy with the strength of a grown man, asked specifically to be there by his grandfather, fell back into Councilwoman Leda’ arms. A spear shaft protruded from the middle of his chest.

Gyles didn’t mutter last words or even make a single sound. The sleek, black spear must have killed him instantly. Bright red blossomed on the front of his homespun shirt, his eyes wide, surprised, and glassy. The pitchfork the boy had been clutching clattered to the floor.

For a long while, there was screaming, crying, consoling, and grief. Leda herself carried Gyles’ body to the end of the corridor and outside, placing him gently on the open ground in the nighttime air. It was Erin Wywood, the minstrel, who knelt over the boy, closing his eyes and singing a prayer to the night stars and moon.

“I– I promised to watch over him,” Leda said in disbelief. “I told Bert.”

“Well, you failed,” Erin paused to say without venom, quite matter-of-factly. It was as if she’d slapped the councilwoman, however, and Leda stumbled away into the night to throw up and sob. Shrugging, dry eyed, Erin continued her song. She had a strong voice, and her mournful tune moved several others to solemn silence.

Bern, meanwhile, tried his best to tend to Umur’s shoulder wound, and managed at least to get the bleeding staunched. The dwarf looked pale and weak now, his voice strained. The others tried to convince Umur to head back to Graymoor, but he set his jaw stubbornly.

“You say me, but we should alla’ go back,” he grumbled. “We’ve found only death here. We’re just simple villagers, yeah? No use in tryin’ to be more.”

“We keep on,” Leda said decisively, stepping out of the shadows. She looked shaken but resolute. “They’ve taken Little Gyles, these bastards. We go in, we take what we can, and we ensure his death was not in vain.”

The group eventually realized that the black, sleek spears were better weapons than any of them wielded. Bern and Egerth were the first to take theirs, and after some discussion the Haffoot siblings, Ethys and Giliam, gripped the other two. The halfling pair, who made their living hauling tea in a small boat up and down the Teawood River, looked particularly small carrying the long, wicked weapons. When offered one, Finasaer Doladris explained that, as an elf, he could not touch the iron of the spears for long, but he did pick up Little Gyles’ wood-shafted pitchfork. Even the scholar, it seemed, had recognized the danger of their situation.

It was Erin Wywood, having prayed over Little Gyles, who recognized that the armor on each statue was not part of the sculptures and could be removed. It took what felt like ages, but together they puzzled out how to unstrap the pieces from the unmoving iron and help each other don them. Umur looked the most natural in the matte, black metal, even though his dwarven physique forced him to exclude some of the original pieces. Hilda Breadon, the stocky baker, followed Umur’s lead and made hers fit in much the same way. Erin donned a full, scaled suit, which the others thought only fair since she had discovered it in the first place. And, thanks to the particular urging of Umur and Bern, Councilwoman Leda took the final suit of armor herself.

When everything was sorted, only the haberdasher Veric Cayfield found himself armor- and weapon-less. He smiled brightly and said that he didn’t mind… it was fun to help get the others fitted into armor, and he would feel ridiculous holding a spear.

“I have my scissors if it comes to fighting,” the halfling announced with halfling cheer, patting a pouch at his hip. “But I don’t think it will. This strange place beyond the portal is full of traps, not monsters. What do you think the traps are protecting, do you figure?” His youthful face brimmed with curiosity.

“And who was the principal architect of this demesne?” Finasaer wondered aloud, tapping his lip. “Fascinating.”

At that, the group grew quiet and began to reenter the corridor from the outdoors. The last one to linger was Erin Wywood. She looked up at the full moon, then at the blue, solitary star called the Empty Star, then back to the moon. The girl touched a pendant hanging from a delicate chain around her neck, that of a silver, crescent moon.

“Shul,” she whispered. “God of the moon. Watch over us, please.”

“You coming, Erin?” Hilda asked from the portal. She saw Erin’s gaze, and followed it up to the sky, settling on the Empty Star.

“Of course,” Erin said, and joined the others.

Back inside and down the corridor, they all looked warily at the closed, iron-banded door between the statues. After the experience of the last two doors and the talk of traps and mysterious builders, no one seemed especially eager to go first.

With forced bravado, Councilwoman Leda told the others to stand aside. “From now on, I’ll go first,” she announced. “Everyone keep sharp and have your eyes open. If you see something, speak up.” The others murmured assent, even bitter-faced Egerth. The smell of sour, nervous sweat filled the room. Leda’s gauntleted hand reached out to the door, she exhaled sharply, and tried the latch.

It clicked and the door swung open. Leda winced, expecting pain. Nothing happened.

Beyond the door was a large, square room with marble flooring and polished walls. At the far end of the space was a towering granite statue of a man. It was a full thirty feet tall, and a detailed work of artistry most of them could hardly fathom. The statue’s eyes looked somehow intelligent, and his barrel-chested body was carved to show him wearing animal hides and necklaces from which dangled numerous amulets and charms. A heavy, stone sword was carved to hang at the man’s hip. He looked both like a barbarian warrior and shaman, though from where or when none of them could even begin to guess.

One arm of the statue was outstretched, its index finger pointed accusingly at the doorway in which Leda stood. After the room with the spear-throwing statues, she quickly stepped into the spacious room and aside.

“Come on,” she said to the others. “There are more doors here.”

Indeed, the square room had three additional doors, all identical to the one they’d just opened, at each wall’s midpoint. Four sides, four doors, one enormous statue. Otherwise, the room was empty.

As everyone slowly filed in, boots echoing on the marble floor, Umur Pearlhammer peered up and around, studying the statue and room’s construction.

“Careful,” he growled. “See those scorch marks on the floor and walls? And look here, this statue weighs tons but there’s grease here on the base where it meets the foundation.”

“What does that mean, master stonemason?” Bern asked nervously.

“It means, methinks, that the statue rotates and shoots fire, yeah?” he rubbed thick fingers in his beard, frowning. “Though the masonry involved in such a thing, well… it boggles me mind.”

“Traps, not monsters,” Veric Cayfield said from the back of the group.

At that, everyone froze and looked wide-eyed up at the enormous barbarian shaman, its finger outstretched accusingly at the empty, open doorway.

“What– what do you think activates it, then?” Ethys Haffot whispered. Still no one moved.

Umur continued rubbing at his beard, eyes searching. “Could be pressure plates on the floor, s’pose, but I donna’ see any. Could be openin’ the doors, but it didn’t scorch us when we came in, did it?”

“Eyes open, everyone,” Leda almost succeeded at keeping her voice from trembling as she called out. “And let’s not clump together.”

For the next several minutes, the ten Graymoor residents carefully, carefully spread out and searched the room. Other than discovering more evidence of fire to support Umur’s theory, they found nothing.

“Maybe… it’s broken?” Giliam Haffoot, the brother, asked, rubbing at his brow with a sleeve. He had twin metal hoops as earrings, and unkempt hair, and both he and his sister’s shirts had dramatic, blousy sleeves. “Been here for years, innit?”

“We have no idea how long,” Bern mused. “We could be standing in another plane of existence, outside of time, even on the surface of that distant Empty Star. That statue could be of the god who created everything, ever, all the stars and worlds. Who knows? This place is a wonder.”

“Now you’re just talking crazy, Bern,” Hilda the baker chided.

“A miracle,” Erin the minstrel breathed, eyes wide. One hand strayed to her pendant.

“Let’s assume,” Umur murmured through teeth still clenched in pain. “That it will roast anyone who tries ta open a door. What do we do?”

They all contemplated.

“We could open all three doors at the same time,” Ethys Haffoot offered, planting the tall spear on the stone to lean on it. “Maybe the statue’ll get confused, then.”

“Or only cooks one of you, at the least, while the others escape,” Egerth the jeweler mused. A couple of his neighbors noted that he said “you” and not “us.”

“And then what? The rest of us run to a door where it ain’t pointin’?” Giliam asked, his scrubby face scrunched in thought. “Sort of a shit plan, though, innit?”

“Do you have a better one, Master Haffoot?” Bern asked. The halfling seemed surprised to be asked and looked absolutely dumbfounded how to respond. Neither he nor the others could come up with an alternate suggestion on how to proceed.

With much apprehension, then, they assembled themselves. Councilwoman Leda would open the western door (none of them knew if it were truly west, but it helped to have a description, so they pretended that the door from which they’d come was south), Umur the northern one, and Giliam surprisingly volunteered for the eastern door. The others of them stood near one of the doors, Bern and Finasaer with Leda, Erin and Hilda with Umur, and finally Egerth and the two other halflings joining Giliam.

“Ready?” the councilwoman called out, placing her hand on the handle of the western door. As she did so, a whirring noise began building within the room. “Now!”

In surprising synchronicity, the three figures at the door clasped the latches and opened their respective doors. As Umur had predicted, the immense stone figure rotated on its base with a sound of grinding rock so deep that they all felt it in their bellies more than heard it. Ethys and Veric shouted warnings, but too late. A fountain of fire erupted from the statue’s fingertip, engulfing poor Giliam Haffoot. The small man shrieked and rolled on the stone as he died.

Veric, the haberdasher with neither weapon nor armor, did not pause. Quicker than anyone there knew he could move, the halfling sprinted on short legs away from the flaming Giliam and towards Umur, diving through the open northern door. Umur, wide-eyed, followed, with Hilda and her rolling pin right on his heels.

“In! In!” Bern shouted over the screams, and he pushed himself and Leda through the western doorway.

Egerth Mayhust, Graymoor’s jeweler, stumbled past the burning, shrieking Giliam Haffoot and into the eastern opening. Then, much to Ethys Haffoot’s utter astonishment, slammed the door closed behind him, right in her face.

The room seemed to shudder as the thirty-foot stone figure pivoted in its base, finger swiveling to the sage Finasaer Doladris, the only elf in Graymoor’s memory.

“No, wait!” he held up his hands, dropping Little Gyles’ pitchfork, before the WHOOSH! of fire jetted from the fingertip to surround him. The elf rolled around in his once-sparkling robes, frantically trying to extinguish the flames. Yet within moments he was nothing more than a burning pile, like Giliam Haffoot across the room.

A Haffoot family trait, the siblings had long told the Graymoor residents, was a single club foot. Both Giliam and Ethys had one, lending credence to the claim. She swiveled her wide-eyed gaze from the western door to the north working out whether she could, on one lame foot, make the distance to either. In a heartbeat she began a galloping trot to the north using the spear as a makeshift crutch.

“Miss Astford!” Veric’s small voice called out once Ethys had made it safely through the door. “Quick! Run to us! So we’re not split!”

Leda turned to Bern at her side and the two shared a quick nod. As one they threw themselves out, leaping over the charred, flaming lump of Finasaer and towards the north. The room shuddered and rumbled as the statue began tracking their movement. Neither she nor Bern even paused to take in the surroundings beyond the western door before exiting it.

Bern, in Mythey’s leathers, sprinted past the councilwoman, around the statue’s base and into the northern opening. Leda stumbled, feeling clumsy in the enameled, black metal strapped everywhere. Before, she’d found the weight of the scaled mail comforting. Now it felt like a boat’s anchor. Ahead, a group of huddled faces, Veric, Umur, and Erin, all reached out from the doorway urging her on.

“Come on!” Umur growled from mere feet away. “Run, lass!”

The others dove for cover as the sound of the flames fountained from behind Leda. Her back and legs seared with heat and she jumped with her last bit of strength towards the now-empty doorway. The councilwoman landed painfully, with a clatter of armor, and suddenly multiple hands were all over her, rolling her and helping to extinguish the flames. Hilda slammed the door shut, leaving only the sound of several people panting and the smell of burnt hair hanging in the air.

For several moments, Leda gasped for breath and lay her cheek on the stone floor beneath her. Her father’s longsword, never used once in her life, jammed painfully beneath her hip. Umur sat gasping, his back against the door. His bandaged shoulder, visible through the gaps in his patchwork armor, was soaked in fresh blood. Bern, Erin, Hilda, Ethys, and Veric all sat or stood nearby, the group stunned and panting. Seven of them remained where they had once been twelve.

Hilda, the baker, was the first of them to become aware of the shimmering, ethereal light in the room. She turned and gasped. “What– what is this place?” she whispered.

III.

The seven remaining Graymoor residents, in wonder, examined their surroundings. The room they found themselves in was rectangular and larger even than where they’d just escaped the deadly, fire-spewing statue. This space was dominated by an enormous pool of water running the entire length of the room. Something shone from beneath the water’s surface, illuminating the polished walls and ceiling with dancing, spectral light. A walkway of stone surrounded the pool, and along the western and eastern sides were several pillars reaching floor-to-ceiling. In the far, northeastern corner stood a closed doorway.

“It’s beautiful,” Hilda said in a low voice. The baker looked incongruous wearing pieces of matte, black armor while wielding a rolling pin in one of her large hands. The shimmering light danced in her wide eyes.

“Yes, but– oh no!” Ethys Haffoot whispered urgently. “Something’s moving. There! Between the pillars.”

They all froze. Indeed, it wasn’t a single humanoid figure moving, but perhaps half a dozen. All the creatures, it seemed, were shuffling their way towards them. The movements were stilted and slow, like a puppet on the end of a beginner’s strings.

Umur drew the short sword from its scabbard. Hands on spears tightened. Veric Cayfield even fumbled in the pouch at his hip and pulled forth a pair of iron scissors.

Leda, for her part, left her father’s sword sheathed. She had never drawn it in combat–never fought with any weapon, really. Instead, she involuntarily made fists at her side, hands shaking, and her back throbbing with pain from the statue’s fire.

The nearest, shambling figure rounded a pillar and came fully into view. It was a human woman, except that she seemed to be made entirely of a translucent crystal. Because of her glasslike nature and the shimmering light, it was difficult to make out too many features. From what they could make out, though, it looked exactly like an armored, barefoot woman transformed to crystal.

“What– what is it?” Ethys Haffoot gasped.

“Traps, not monsters,” Veric whispered fervently. His hands were shaking, the scissors bobbing in the air in front of him. “Traps, not monsters. Traps, not monsters.”

The crystal figure approached Erin, who reached out a hand in awe and touched its unmoving face. The animated sculpture crowded closer, seeking the minstrel’s outstretched fingers. Everyone else tensed.

Then Erin’s freckled face split into a wide smile, an uncharacteristic expression for the overly-earnest girl. “They aren’t dangerous, are they? More like a stray dog needing attention. Why do you think they’re here? What is this place?”

Slowly, haltingly, the other crystal figures came nearer. They stood near the group of Graymoor residents and otherwise did nothing. It was a mixture of male and female sculptures, and the detail from whoever sculpted them was astounding. Up close, the villagers could see individual folds in cloth, and each face had its own distinct personality.

Umur edged away from them, close to the pool’s edge, and peered downward.

“Looks like jewels or gems of some kind,” he said gruffly, but his voice was tinged with amazement. “On the bottom of the pool. Glowing gems, if I’m seein’ it clearly.”

“I wish that our jeweler Egerth was here,” Bern Erswood said. In his leather armor and holding a spear of jet black, he looked the most like a warrior of any of them. The well-liked herbalist squinted, trying to see though the shimmering water clearly, then looked up to the group. “Where is Egerth, by the way? Did the fire get him?”

“No,” Ethys Haffoot said, the single word dripping with venom. “Selfish bastard watched Giliam die and closed the door in me face.

“Should– should we go back? Find him?” Veric asked in a small voice, not standing on the pool’s edge but stroking the back of a crystalline figure like one might a cat.

“No,” Ethys replied immediately. “He deserves whatever he gets. Bastard!” And then the young halfling burst into tears.

Councilwoman Leda moved to embrace her, and Ethys melted into the hug. Ethys cried for several minutes, face buried in the woman’s enameled, scaled breastplate, while Leda patted Ethys’ twin braids.

“I’m sorry about your brother,” she said gently. After a long while, Ethys stilled and sniffled, pulling herself from the councilwoman and nodding in thanks.

Hilda stood next to Umur and the two of them continued to peer into the water. “If those are jewels, shouldn’t someone dive in to get them?” she asked. “Isn’t that what Old Bert said? We could change our fortunes? It doesn’t look so deep.” She looked around at the others helplessly, eyes pleading and clearly not interested in exploring the water herself.

“I can do it,” announced Ethys, wiping her nose with a sleeve. “Even with me foot, I s’pose I’m the best swimmer here.” It was true, they realized. Ethys and her brother had spent their entire lives up and down the Teawood River.

“If Veric is right,” Umur grumped. “This smells like a trap t’me. Soon as you dive in, lass, I suspect these statues’ll be a lot less friendly. Or somethin’ else more horrible.”

“It’s worth it, though, yeah?” Ethys said with chin raised proudly. “We can’t have come here for nothin’.” And without further conversation, she handed her tall spear to Erin and dove gracefully into the pool.

As Ethys’ body disappeared below the water’s surface, the statues did not move or change their behavior. Neither did the chamber fill with poisonous gas, spikes drop from the ceiling, or any number of other visions that filled the villagers’ imaginations. Instead, after a dozen heartbeats Ethys gasped to the surface. She was grinning as she swam leisurely to the pool’s edge, legs moving like a frog.

“With me knife I got a couple free!” she announced, tossing them to Umur’s feet. “Must be hundreds of them down there. Be right back!”

Umur knelt, grunting with the effort, and plucked one of the jewels from the floor. Hilda picked up the other one.

“Looks valuable, yeah?” Hilda whistled. Umur grunted in assent.

Ethys was indeed a capable swimmer. She stayed below the water far longer than the others likely could have managed, and each time she surfaced she tossed more beautiful gemstones to the floor at their feet. What was initially two jewels became ten, then twenty, and each one a luminescent white and beautiful.

The halfling mariner surfaced, paddling closer to the edge and for once not depositing any treasure to the pile.

“Is that all you can pry loose, then?” Hilda asked, marveling at the gems in her meaty palm. “A good haul.”

“Oh, I could get all of ‘em,” Ethys said, looking worried. “Only, I think pryin’ ‘em loose is doin’ somethin’.”

“Doin’ what, then?” Umur frowned deeply, thick fingers scratching at his beard. His eyes scanned the chamber in alert.

“I think– I think the water’s drainin’ out,” Ethys replied, swiveling her head up to the dwarf. “I’m leavin’ holes on the bottom of the pool.”

As she said the words, they all realized the truth of it. The pool was already several fingerspans lower than it was when the brave halfling had first jumped in, and there was an almost imperceptible hum of water like a drain in a washtub. Councilwoman Leda turned to Umur. “What does it mean, master stonemason? Anyone?”

The room looked back at her, blank-faced and shrugging. Certainly, the crystalline figures hadn’t changed their behavior; the translucent creatures huddled near members of their group passively and silently, seemingly unperturbed by either the stolen jewels or draining water.

“I suppose the water leaving is a good thing, then,” Hilda offered hesitantly. “It means it’s easier to reach the gems, right?”

“Alrighty, then,” Ethys said, and disappeared again beneath the surface.

For several more minutes, Ethys did her work. Leda and Bern, meanwhile, joined Umur in scanning for danger, her standing by the dwarf’s side and him wandering around the pool’s perimeter. Erin and Veric spent their time talking and interacting with the crystal figures, to no obvious effect. Hilda, meanwhile, never took her avaricious gaze from the growing pile of jewels at her feet. With wonder, the baker knelt and ran her fingers through the gemstones, counting quietly.

“That’s forty-five of them,” she breathed excitedly. “We’re truly all going to be wealthy, aren’t we?”

Umur grunted skeptically.

Bern, meanwhile, had made his way to the northeastern corner of the long, rectangular room, where the second door stood closed.

“Should I open it?” he called in a low, loud whisper.

“Absolutely not!” Umur’s bushy eyebrows climbed his forehead. “By the gods, man! Once Ethys has the rest of the gems, we leave! We’re not heroes!”

At this point the water level in the pool was only knee-high. Rather than dive, Ethys stooped down to work her knife. When she had another handful, she straightened to her full height, dripping, to make her way back to the pile at Hilda’s feet.

“Five more for ya,” she grinned. It’s getting easi–”

Her words cut off as a giant THUNK! echoed in the chamber. Ethys cried out as she stumbled. Everyone’s eyes bulged with alarm.

“What was that?” Erin gasped.

“The floor–” Ethys splashed her way, stepping with high knees, to the shallow pool’s edge. “It buckled! I think pulling the gems is making it weaker or–” And then another THUNK!

Hilda frantically grabbed as many loose gems from the floor as she could manage. Ethys deftly swung up and grabbed a large piece of folded sailcloth she’d brought, helping collect the shining jewels.

“Hurry, hurry!” Hilda yelled. “Help us!”

Leda and Umur rushed to comply, but Erin and Veric were rushing north to Bern’s side.

“This way!” Bern yelled to them across the chamber. “I’ve opened the door! It’s a stairwell!”

Leda was about to argue that they should escape the way they’d come, but then a sudden vision of that enormous statue, finger outstretched, filled her mind. She cursed.

“Let’s go. Follow Bern,” she urged. Umur helped her up, both wincing in pain from their earlier wounds. A quick glance and she saw that the water was almost gone now, draining quickly out of the holes left by fifty missing jewels. “We should hurry,” she panted.

As they all rushed to the doorway, the crystal figures shambled haltingly, following. They moved at a quarter of even the club-footed Ethys’ speed.

“Do we wait for them?” Erin asked, concern in her eyes back at the crystal figures.

There was another shudder from the pool’s floor, echoing.

“No,” Councilwoman Leda said with finality. She slammed the wooden door shut behind her.

As Bern had described, a spiraled staircase awaited them all, plunging down into darkness. Something from the pool room crashed and boomed.

They descended.

IV.

“I can’t see anything,” Hilda Breadon gasped in the darkness. “We– we have to stop.”

Seven Graymoor residents bumped into one another in a halting, huddled column, all breathing heavily from the surge of fear from escaping the pool room.

“Does anyone have a torch or lantern?” Councilwoman Leda asked. Her burned and painful back pressed against the rough stone of the wall through her black-scaled armor, seeking solidity and support in the dark.

“The halflin’s an’ I don’ need it,” Umur panted. “But this might work for the rest of ye.”

Soft white light filled the space as the dwarf opened his palms to reveal the glowing jewels Ethys had retrieved.

“Ah,” Hilda chuckled. “Ya, those work.” Soon more light spilled into the cramped staircase as she held a handful of the beautiful, spectral gems.

Ethys followed suit, then the councilwoman. They passed stones to Verik, Erin, and Bern. Soon all of them had at least a few of the luminescent jewels, which banished the shadows as well as any torch.

They stood on a descending, spiraled staircase, the stairs wide enough that they could almost walk two abreast without their shoulders scraping against the stone. Almost, but they assembled themselves single file to proceed down to the lower level of this palace-beyond-the-portal. Councilwoman Leda maneuvered herself to the front of the line. Umur and Bern followed protectively behind her, gripping weapons in one hand, glowing jewels in the other.

At the bottom of the stairs, the residents found themselves in a long, narrow room, perhaps ten steps wide and five times as long. A door, iron-banded and wooden as all the others, stood firmly closed at the far end of the room. The room itself was bare except for ledges that ran the length of the long walls. Veric, short even for a halfling, stood on his tiptoes to peer up and into them.

“Um,” he whispered in a small voice. “What are those in– oof! What are those in there?”

Bern raised his handful of the glowing gems near the ledge and squinted. “Huh, good eyes you’ve got there. Little soldiers. Made of clay, if I’m not mistaken.” He plucked one from its place and handed it to the haberdasher. Veric made a pleased sound as he turned the soldier over in his hand.

As the group moved towards the door warily, Hilda lingered behind. Tongue lodged between her lips in concentration, she brought the glowing jewels up to peer into the ledge nearest her. Her eyes darted left and right, scanning the clay figures. The baker quickly let out an excited yelp.

“I found some silver ones!” she whooped, not at all whispering. Hilda had to tuck the rolling pin into an armpit as she displayed what she’d discovered. Sure enough, they were small figures of soldiers, like the one that Bern had handed to Veric, each as long as a finger. Yet the four Hilda held up gleamed metallically.

For several minutes the other humans searched the ledges, but to no avail. Hilda had spotted the only obvious treasures and seemed none too eager to give them up. She proudly tucked the figures beneath her breastplate and blouse, smiling broadly the whole time. “For safe keeping,” she chuckled, patting her armor.

“Away with us then,” Umur grumbled. “See if tha’ door can lead us out or if we ha’ to go find out what all the crashin’ was about upstairs.”

“I’m certainly ready to leave,” Councilwoman Leda nodded. The others agreed, and, with a quickly held breath, Leda opened the door.

The room beyond was as breathtaking as it was intimidating. As large as the room with the giant statue and the pool room combined, the cavernous space was thrice tiered. An oversized throne rested upon a raised dais at the back, and seated upon the throne was a large clay statue. The warlord on the throne looked to represent the same person above that spewed fire from its fingertip–barrel-chested and wearing animal hides and charm-laden necklaces, with a heavy sword at his hip. The deadly stone statue above had been thirty feet high, and this clay one was perhaps half that size and seated, yet no less intimidating. Atop the throne, light pulsated from a crystal globe, illuminating the entire chamber. Absently, mouths agape, the residents tucked the glowing jewels away.

“That orb is sure pretty,” Hilda mumbled to no one in particular.

Below the dais, at floor level, seven other clay statues–these taller than a human but smaller than the figure on the throne–stood motionless. Each looked fierce and distinct from the others, carrying a variety of clay weapons in menacing poses. Below them, in a huge sunken pit that ran the length of the room, stood an army of clay soldiers, all the size of a human, their identical clay armor and spears seemingly ready for war.

The ceiling above had partially collapsed, sending debris and water into the sunken pit. Carnage from the collapsed ceiling had settled, though dust still drifted through the air. Many of the clay soldiers lay broken or canted to one side, and all of them were slick and in various ways like melted wax, presumably from the water that was now a pond at their feet. The pool room, they realized, must have been directly above this one, and the crashing they’d heard earlier had been the collapse. A pang of guilt ran through Hilda, Erin, and Bern at the thought that they had utterly ruined not only the beauty of the shimmering pool, but this majestic statuary garden. Councilwoman Leda, however, could see only Little Gyles’ dead, empty stare and cared nothing for the carnage before her.

Suddenly, the large figure on the throne jerkily and mechanically raised its arm, pointing at the doorway in which Veric, bringing up the rear of their line, stood. In reaction, the seven figures at floor level snapped to attention and mimicked the gesture, their fingers leveled at the party of villagers.

And then, with a yelp from Veric and scream from Hilda, the entire army of damaged clay soldiers lurched into motion.

Quick-witted Erin Wywood, town councilor’s daughter and local minstrel, was the first to act. While the others stood goggling at the army rising up before them, she kicked at the lip of the pit into the head of a rising clay soldier. Like a log briefly surfacing in swamp water and then sinking below, the soldier toppled backwards and into the soldiers crowding behind.

“Get to the one on the throne!” she yelled at the others. “It’s controlling them!” Against all sense of reason, the girl then began jogging her way around the edge of the pit, deeper into the room, as clay soldiers rose up all around her.

Veric, wide-eyed and clearly near panic, followed close behind her. As he passed a rising soldier he flailed with his iron scissors, missing it by a country mile. Cursing and screaming, Hilda was right behind him.

Without realizing she was doing so, Councilwoman Leda Astford pulled her father’s longsword free of its scabbard. Yelling in fear and pain, she swung at the first clay soldier climbing out of the pit nearest her. She had never swung the sword, however, and misjudged its length. The blade sailed in front of the oncoming figure ineffectually.

Clay soldiers were boiling out of the pit on all sides, many missing arms or large chunks of their heads from the fallen ceiling, with legs soft and distorted by the water filling the hole. Some within the pit listed and fell without rising again. It was chaos, and every one of the Graymoor residents yelled or screamed in visceral peril.

Roaring, Umur lashed out with the shortsword he’d plucked from Mythey’s corpse before even entering the portal. How long had it been, he wondered abstractly. Two hours? More? The dwarf cleaved an oncoming soldier nearly in two as it toppled, inert. To his right, Ethys and Bern stabbed in tandem with their spears, pushing two soldiers off the ledge of the pit and into the muddy slurry below.

Out at the edge of the pit, halfway to the warlord sitting motionless atop his throne, Erin swung wildly and then, panting, stepped back. Veric leapt forward, both hands holding the ends of his scissors, and plunged them into the clay head of a soldier while Hilda bashed one aside with her rolling pin. Soldiers crumpled and slumped, even as more used their bodies for purchase to climb out of the pit.

Councilwoman Leda faced a trio of soldiers. The grip on her father’s sword was slick with sweat, but she had the balance and length of the weapon now. Drawing inspiration from the others, she screamed and cleaved a soldier’s head from its clay body.

She shouted triumph as the soldier fell to one side. In that moment, Leda felt like a warrior of old, black-scaled armor shining under the light of a mystical orb as she struck foes with her ancestral longsword, all while some alien warlord god looked down from his throne. She wished her father could see her now, like an avenging angel of battle.

“Ha! Did you see, Umur?” she shouted, then felt a sudden, sharp pain in her back.

“No!” Umur yelled, eyes wide. Leda looked down, confused, to see the clay spearhead protruding from her chest, and then thought nothing at all.

Erin watched the councilwoman fall to her knees and then face-first to the stone floor, a clay spear protruding from her back. Umur was swinging his sword, beating back soldiers as they crawled out of the pit in a vain attempt to reach her fallen form. Bern and Ethys were near him, stabbing with their black spears. Ahead of her, Hilda swung her rolling pin and Veric his scissors.

But a tidal wave of soldiers were climbing up ahead of them all, blocking the way to the warlord on the throne. The odds were impossible, and Erin realized with fatal certainty that they could not survive the dozens of clay soldiers.

Using a voice honed by countless hours of singing, she called out across the cacophony of battle. “Into the pit! Dive into the pit!”

Dagger in hand, Erin took her own advice. She leapt into the pit, stumbling in the knee-high water across ceiling debris and half-dissolved clay figures. The minstrel moved away from the edge and any spear thrusts. A splash from Veric signaled that he had followed her lead, and then a thunderous crash and whoop as Hilda joined them.

The three shouted for the others to follow. Ethys dove as nimbly as she’d done in the pool above, despite the shallow water and debris. Umur, roaring, landed directly atop a soldier in the pit. The impact of dwarf on soft clay utterly crushed the thing.

Bern readied his leap, but not before a spear clipped his side. He turned to face the soldier attacking him, which allowed another soldier to jab out. The herbalist died under a barrage of blows, mere fingerspans from the edge of the pit.

The clay soldiers that remained in the slushy, muddy pond had lost much of their cohesion and moved sluggishly, but they were still threats. Erin ducked under a swing from one. Hilda blocked another spear with her rolling pin.

“Veric! Behind you!” Ethys yelled out. The haberdasher spun and made a brief squeal as the spear thrust through his neck. Soldier and halfling went down beneath the water’s surface.

The flood of soldiers had become a trickle. Several slogged slowly towards them, but often the water took their legs and they fell face-down into the slurry. Other clay soldiers moved from the pit’s edge back in. Their numbers were manageable now, though whether the ongoing damage from the water would destroy them before they impaled the remaining villagers remained to be seen.

Two soldiers made it to either side of Hilda. As they pulled back their spears to attack, they slumped like melting candles.

“Keep going!” Umur urged them on, though he labored with his wound and fatigue. “To the back! To the throne! Keep them in the water!”

Panting, laboring, and terrified, the four Graymoor residents slogged their way to the far southwestern corner of the pit. Clay soldiers moved awkwardly towards them, stumbling, falling, and never rising as they went. Eight soldiers became six, then four, then two.

A mere handful of feet from the villagers, all huddled in a corner with weapons raised, the last soldier collapsed.

Without pausing, Erin pulled herself up and out of the muddy mess. Hilda followed, then turned to pull Ethys and Umur up.

“Careful,” the minstrel cautioned. “Now the generals might attack.”

At this alarming statement, the others leapt to a defensive formation, weapons ready.

But nothing moved. The warlord on his throne and generals assembled at his feet had been merely the catalysts to activate the clay army. The statues simply stood, fingers pointed accusingly at an empty doorway far across the cavernous room. That is, until the residents of Graymoor destroyed them with repeated blows to their clay bodies. Eventually, not even the giant warlord on the throne remained.

Only then did they relax, hands on muddy knees. Of the twelve who’d assembled around the portal beneath the stars, only four remained.

V.

“The moon is barren,” Erin Wywood sang with her mournful, strong voice, clutching the charm around her neck fervently, head bowed and eyes closed. Her companions, now only Ethys Haffoot, Hilda Breadon, and Umur Pearlhammer, surrounded her in silence. All of them were caked in dried mud and blood.

“The moon is old.

“The moon is knowing.

“The moon is cold.

“Its light a mirror,

“And moves our souls.” The minstrel opened her eyes as this last word lingered, and they were brimming with tears. She looked around at the bodies arrayed before their small gathering. They had worked together to drag them here, at the foot of the giant throne.

“Leda Astford. Bern Erswood. Veric Cayfield. May these souls find you in the heavens, Shul, God of the Moon, Dancer of the Half-light Path, Husband of the Three. May you also shepherd Giliam Haffoot,” at this Ethys choked a sob. “Gyles Teahill, Finasaer Doladris, Mythey Wyebury, and Egerth Mayhurst.”

The halfling snarled. “No! Not him. Let Egerth burn in an undying hell.”

Erin sighed and nodded sadly at Ethys, which seemed to mollify her. “May these souls find rest in your domain among the stars, and may you find good use for them in your celestial domain. May your light banish the Chaos in darkness and remind us of a brighter day. May it be so.”

“May it be so,” the others repeated.

Erin released the silver crescent moon in her grip. “Alright,” she said wearily. “Thank you all. Now, do we explore the door that Umur found behind the throne, or do we leave this place as best we can? There are only four of us now. It should be a group decision.”

The others cleared their throats and looked around the vast chamber. Shattered clay pieces and slabs of mud were everywhere, littering the throne, floor, and shallow water of the pit below them. Only hints at the vast army of soldiers remained; clay arms, hands, broken spears, and half-heads were scattered around the floor. In the pit was only brown, thick water and chunks of the ceiling above.

“You said you thought the door led to treasure, didn’t you Umur?” Hilda asked. She had dropped her rolling pin and held in both hands the glowing orb from atop the throne, big as a small watermelon and seemingly made of pure crystal. This close, the pulsating light was harsh and cast deep shadows on Hilda’s face and arms.

“It’s me best guess,” the dwarf sighed. “Whoever built this place would hide the vault behind the throne. But, mind, it could be trapped as well. The door was not easy to find.”

“I suspect it is trapped,” Ethys frowned. “Everythin’ in this cursed place is trapped, eh?”

“I agree,” Erin conceded. “We have jewels from this place we’ve salvaged, silver figurines, and a magical orb,” she nodded at Hilda. “Plus armor and spears better than anything we could forge in Graymoor. It’s enough, isn’t it?”

Hilda frowned, clearly the dissenter. She looked at the others in turn, then eventually puffed out her breath in a mighty heave.

“Alright, alright. We leave it. I’m sure you’re right that it’s trapped, and we’ve seen enough death to last our lifetimes. Imagine what this place could be hiding…” emotions warred on the baker’s face. “But okay. Alright. We leave it.”

Erin nodded. “And we do not explore the rooms on either side of the giant statue, either, not the one Councilwoman Leda and Bern opened, nor the one Egerth disappeared into. We are retracing our steps as best we can and getting out of here. Yes?”

“Okay, but how are we getting past that giant statue without getting burned alive?” Ethys asked, tamping the end of a black spear on the stone.

“I’ve been thinkin’ on it,” Umur said. “May have an idea there.”

The dwarf had strapped Councilwoman Leda’s ancestral longsword to his belt on the opposite hip from Mythey’s shortsword. He, Hilda, and Erin all wore the black-scaled mail from the spear-throwing statues. Ethys declined to peel the armor from Leda’s corpse, but she was happy to take Bern’s spear and have two of the weapons. Erin, meanwhile, had taken Veric’s iron scissors, not as a weapon or tool but as something to bury when they returned to Graymoor. They had all agreed that they couldn’t realistically bring the bodies of the other residents with them.

“Let’s go then,” Umur announced.

Slowly, painfully, the four companions made their way from the large throne around the pit and out the way they’d come. Hilda glanced back at the throne, where a door lay open behind it, and sighed heavily. Then she followed.

The pulsing orb banished the darkness in the long, wide room containing the miniature clay soldiers on its ledges. As they passed through it, Ethys wondered aloud.

“Who built this place, then? That guy from the statues… seems a wizard, yeah? But also a warlord. Where is he now, d’ya think?”

“I don’t suppose we’ll ever know,” sighed Erin. “Some knowledge is not meant for mortals.”

Hilda harrumphed at that, disagreeing but choosing not to say so explicitly.

“Quiet now,” Umur growled. “We don’ know if the room with the pool is still there, or what effect it’s had on those crystal people.”

They climbed the spiral staircase to the closed door at its top, which Umur opened hesitantly. The room was indeed still there, but no longer lit by shimmering gemstones beneath rippling water. Instead, Hilda’s orb showed that the long, rectangular pool had fallen away below, but the rest of the floor was intact. Stone walkways interspersed with tall, floor-to-ceiling pillars, allowed them to stay wide of the now-gaping hole where the pool had been.

The crystal figures remained unharmed, and they shambled their way towards the companions. Erin hoped they could bring the strange creatures with them to Graymoor, but once they moved towards the door to the giant statue, the crystalline humans edged away like frightened animals. They would not step closer than five strides from the exit, and nothing the companions tried could convince them otherwise.

“Do we force them, then?” Hilda asked.

“No,” Erin sighed. “I suppose we leave them here, in their home. Like everything else in this place, I have no idea if that’s the noble decision or not.”

“I’m still wonderin’ how we aren’t gonna be cooked by the statue,” Ethys muttered.

“Calm yerself, lass,” Umur grumped. He was wheezing in pain from his shoulder wound and a mosaic of smaller hurts. Mud caked his broad beard and armor. “I’ll go first. This is all based on it not cookin’ me when I first open the door. If it acts like it did when we first arrived, though, I’ll try me idea.”

The dwarf placed a bloodied, dirty hand on the latch and pulled. The door opened.

There was the enormous stone statue, dominating the square room. Its outstretched finger pointed directly at the doorway in which Umur stood.

After several heartbeats, the dwarf exhaled. “Alright, good. Let’s go then.”

Ethys hobbled in on her club foot and made her way to the burned lump that was once her brother. She sank to her knees, dropping the two black spears in her hands, and wept. Erin lay a hand on Umur’s uninjured shoulder.

“I’ll go be with her,” she said in a low voice. “What’s your plan, Master Pearlhammer?”

“I need to look at the base,” he said. “And I need one’a those spears.”

Erin nodded, leaving him to examine the base of the enormous statue. Hilda followed Umur, providing light with her glowing orb. Their footfalls and Ethys’ sobs were the only sounds in an otherwise silent space.

Without saying a word, Erin plucked the spear that was briefly Giliam Haffoot’s from the floor and brought it to Umur. Then she returned to Ethys and crouched down at her side. If the minstrel had prayers to her Moon God at the ready, she chose to reflect on them silently. Instead, she merely sat with the halfling while she cried and shuddered with grief.

A long while later, the light from Hilda’s strange orb grew closer. Umur stood at her side.

“I’ve done it, then,” the dwarf said, clearing his throat. “We can go now, or at least try.”

Ethys sniffled and nodded. As she rose stiffly, she hugged Erin tightly for several heartbeats. When she let go, Ethys looked up gratefully.

“Thank you,” she whispered. Erin nodded, a sad smile on her face. A memory flashed of Leda comforting Ethys immediately after her brother’s death, and a pang for all they had lost today ran through the young woman.

“So,” Ethys said shakily. “What’s the plan, then?”

Hilda answered for him. “He’s hammered one of the spears in the place where the statue rotates,” the baker said proudly, as if she’d done the work herself.

“Do you think it will keep it from turning?”

Umur shrugged, then winced in pain at the motion. “Hard to say. But it should at least give us time to leave. The exit is the opposite of where he’s pointin’, so even if it just slows the thing we can make it.”

They all wandered over to inspect the dwarf’s handiwork. Indeed, one of the black spears now jammed into the crease between the statue and its base. The stone around the shaft had been chipped away to give the spearhead better access to the mechanisms within.

“Are we sure we don’t want to explore the side doors, then?” Hilda asked, then blinked at the dark looks the other three immediately shot her. “Alright, alright. Let’s go home.”

They assembled around the southern door, with the statue’s broad back looming above them from the center of the room.

“When I place me hand on the door, crowd forward. I don’ know how much time I bought us.”

They all nodded.

“On one,” the dwarf rumbled. “Three. Two. Go!”

He threw the door open as the statue began to turn. A sound like a mallet striking a large iron rod echoed in the hall, then again, then a mighty CRACK! that set everyone’s teeth on edge. They pushed through the doorway and, Umur and Erin slammed it closed. Beyond the door they heard the telltale hiss of the flame from its fingertip. The door grew hot, and they all stepped away, panting.

None of the others had ever seen the dwarf whoop in joy, but he did so now. The relief of surviving the warlord’s death trap was palpable, and for a while they all hugged and cheered and, eventually, cried again.

“That’s it, then,” Hilda beamed, cradling her orb with both hands. “We can go home now.”

“If the portal’s still open, ya,” the dwarf chuckled.

At that statement they all grew immediately silent.

“What?” Ethys stammered. “Do you think it may have closed?”

“I… uh,” the dwarf said delicately, scrubbing at his beard with one hand. “It only opened with the star directly overhead, so I don’ know.”

“There is only one way to find out,” Erin said soberly. “And I believe it will be open. We’ve done all of this under Shul’s watchful gaze. It won’t have been for naught.”

The others clearly did not share the minstrel’s faith, but they hustled to the door facing them. Lining the wall behind were statues with arms cocked back, now armor-less and without weapons.

Umur did not pause for ceremony. As soon as he’d reached the door he unlatched and threw it open.

A long hallway greeted them, and at the corridor’s end was a blue-limned, shimmering doorway with night sky beyond.

The air felt cooler and crisper than they remembered. The villagers laughed and hugged again as they made their way outside, then grew more sober as they saw the bloody body of Little Gyles and the burned, stripped corpse of Mythey.

For her part, Erin Wywood looked up at the blue star, what Old Bert Teahill had called the Empty Star. It twinkled and gleamed overhead. Then her gaze shifted to the full moon, bathing the old stone mound with pale light. Indeed, for the first time she realized that the orb Hilda held was like its own miniature moon and would banish shadows wherever she brought it. In that moment, the full divinity of their harrowing, miraculous experience flooded her. She felt without a doubt the divine guidance of Shul steering her and her companions’ movements, from agreeing to join Leda’s expedition earlier in the day to now.

“Thank you,” she whispered to the sky. Then, with newfound appreciation, she looked to Umur, Hilda, and Ethys, all tear-streaked and inviting her to join them.

Under the light of the full moon and Hilda’s orb, Empty Star twinkling blue overhead, she did so.

VI.

a.

Hours later, long after the Empty Star had moved its way across the starry sky and the companions had limped home, the ravaged body of Egerth Mayhurst lay sprawled in a wide pool of dried blood across a stone floor.

The room itself was a rectangle, a fraction the size of the one outside its lone door, where the giant statue pointed its accusing finger. This room’s walls were adorned with seven shrouded alcoves around its perimeter. Next to each alcove hung a primitive funeral mask, each distinct but shaped and painted to look more simian than human. Within these seven darkened burial chambers, pristine weapons, shields, and scraps of armor lay alongside ancient skeletons. Such were the full contents of the room: Seven masks hanging outside of seven alcoves, each with a long-dead warrior within, and Egerth’s bloody corpse.

Even if the once-jeweler had discovered the weapons, it is unlikely they would have saved him from his grisly fate. Egerth’s murderers had been both swift and thorough. His blood-soaked clothes were ripped everywhere, revealing jagged claw marks on the flesh beneath. His chest yawned open, shards of bone reaching to the ceiling around a jagged hole where his heart had been. An arm lay near his torso, unattached by anything but a line of gore. One leg had nothing below the knee, and the other bent at an unnatural angle. Half of Egerth’s shrewd face was gone, including his bearded jaw, but the one remaining eye bulged in horror as it stared vacantly upwards at nothing.

Most conspicuously, seven trails of blood and tattered flesh spread out from the wide, crimson pool, each disappearing into one of the alcoves.

Egerth’s body lay like that, untouched and rotting, as the funeral masks stared down with simian patience.

It would be days until a broken finger twitched, and the corpse began to moan.

b.

Fire crackled and Umur Pearlhammer regarded it silently, unblinking. His dwelling differed from most Graymoor residences, with its stone construction, arched doorways, large entry hall, and sizeable hearth. To Umur, the house reminded him nostalgically of his youth spent below the earth. Never mind the cramped bedroom and kitchen, or the lack of windows that made it seem more cave than house. The space suited him.

It had been a week since Old Bert’s blasted portal, with its treasure and mysteries and death everywhere. Each day since, late in the afternoon, he’d gruffly fled the constant chatter, the mourning and marveling, the requests to tell the “story of that night” for the hundredth time. Insistently alone, he would quest about the Graymoor outskirts for dry wood. By nightfall he would begin the fire, larger and hotter than necessary for the season. Then Umur would spend the long, dark hours watching the flames in contemplation, orange light dancing across his grim, sweating face.

Arrayed across the floor between the hearth and his feet were several items that he had not touched in a week. A full suit of ebon mail lay in pieces, its scales matte and unlike anything he’d seen forged below ground or above. The helmet looked to Umur like the top half of a charred demon’s skull, a single piece of black metal with horns curving from either side and a fluted nose guard. Scattered amidst the armor were jewels, gleaming white in the firelight. And there, nearest Umur’s touch, the cruciform hilt and pommel of the Astford family’s ancestral sword, the blade sheathed in a worn, leather-strapped scabbard. Leda had no living family to whom he could return the weapon. It was his now, everyone insisted, like the other items splayed out before him.

Anyone looking at the white-haired, gnarled dwarf would conclude that he was grieving the councilwoman and all the others in his own way. No doubt that’s what his neighbors believed, and why they gave him unmolested privacy each night and greeted him so tenderly the next morning when he emerged from his stony refuge.

They could not know that in truth a war was being waged within Umur Pealhammer’s heart. On one side of the war were awful memories, memories of chopping the softened heads from clay warriors in desperation, of friends’ death rattles as they choked on their own blood, of the ripe smell of fear all around him, and of the sharp pain as a black spear protruded from his shoulder. These memories, all recent, mixed with older ones, of men with the heads of beasts dying on the ends of dwarven halberds, of cleaving a tentacle the color of a bruise with his axe as it squeezed the breath from him, and of the awful, keening screams of his family as they burned from magical fire.

Warring with these memories within Umur’s heart were visions, and the unrelenting pull of his calloused hand towards the hilt of Leda’s sword. He saw himself caked in iron and gore as he drove Leda’s blade through the last, vanquished beast man. He heard his own voice, raw with passion, singing a dwarven battle hymn as he mowed the forces of Chaos down before a castle wall. He smelled gold and ale in staggering amounts as his allies deafened him with their cheers. And the vision he returned to again and again, like a thread weaving together the tapestry, was of returning to Arenor, the Republic of the Sapphire Throne, to restore his family’s name.

So it raged, the war between traumatic, painful memories of what had been, and bold, glorious visions of what could be. Umur had thought the war over, that he had long settled on his path. He had been content, in a way, hadn’t he? And then came that blasted portal, stirring every dream he’d thought forgotten. Blast Old Bert and blast himself for joining Leda’s flight of fancy. Surely he was too old now to wield a sword, wasn’t he? Except that he’d survived the portal, and the others credited him for his clear head and leadership, saying that he was a key reason any of them had lived. Perhaps, then, he wasn’t too old for those visions to become real. Perhaps.

Umur watched the flames dance in his eyes. His face was as impassive as stone, his eyes unwavering.

It was his hand that betrayed him, clenching and unclenching, eventually reaching for the sword.

c.

By dawn’s light, Ethys Haffoot walked to the small, rickety plank that Graymoor called a dock. Her right foot curved like a crescent moon and caused her to swing her hip, a distinct and uneven gait characteristic of her entire family. Not that Ethys had any family left, really. She sighed at the thought.

Her little skiff sat gently bobbing in the Teawood River, empty. In days gone by, her brother Giliam would already be there, tying down their gear to the flat bottom, making as much room as possible for the crates of tea leaves that they’d pick up from Teatown far upriver. She knew well that everyone considered Ethys the brains of their hauling business, but Giliam had been the heart of it, always awake before the sun and working until he collapsed at night. The vivid image of her brother’s face, covered in sweat and smiling, caused her to stagger and stop a moment. For the thousandth time in the past month, an unexpected sob tore at her throat and vanished as quickly as it had arrived. She wiped her eye of the single tear that gathered there.

“I– I can’t do this,” she growled to herself. “Dammit all but I can’t.”

Thanks to the portal beneath the Empty Star, Ethys did not need the coins from hauling tea. Her handful of glowing jewels would get her anything the village could offer, never mind the goodwill of grateful and pitying neighbors who were all too eager to provide her free food, drink, and shelter, the only price another story from that fateful night.

Even if she’d wanted to continue her excursions, though, she could not have done the job alone. She needed Giliam, or someone else who could provide little enough statue to fit in the small craft, tireless labor, and good humor. Ethys could almost—almost—imagine posting something in Teatown and finding a halfling who might have interest in experiencing the human world downriver. Every time she thought of it, though, a deep wave of fatigue filled her body, sometimes so strong that she would yawn and find a place to nap. No, there was no joy in continuing the life she had led here. Her normal life had died with Giliam, by fire from the outstretched finger of an alien warlord.

What, then, was her life? She couldn’t stay in Graymoor, but the thought of returning to Teatown to live out the small life it offered, with halflings who’d never been beyond the town’s borders, made her want to scream. Neither place held her future, whatever new life lay beyond Giliam’s death.