Game number four of my deep-dive exploration of superhero games that can be played in a fantasy setting. Sometimes I wonder what’s wrong with me, that this is how my brain works.

By now you’re aware that I’m envisioning a new solo-play venture, one that involves a genre mash-up and thus a particular set of requirements for choosing my next game. These by-now-familiar requirements are:

- A superhero game that can be played in a fantasy setting, plus allow for anachronistic weapons and technology. Basically, the superpowers and fantasy elements need to be satisfying, but allow for other genre shenanigans.

- Is neither too crunchy (if I’m consulting forums or rulebooks more often than writing, that’s bad) nor too lightweight (I need to feel like the dice are guiding the story and enhancing the narrative). I want to feel like the mechanics support the story.

- Level-up jumps in power. My idea is that the PCs start as “street level” heroes and become demigods as the story progresses. Something will be pushing them closer to godhood, which is a core part of the story. The game should not only allow for those different levels, but be fun to play at all of them.

- No hard-wired comics tropes (like secret identities, costumes, etc.). The story will be a genre mash-up, so I can’t hew too closely to any overly specific formulas.

After three narrative-light systems in a row, it’s time to turn to something different. Today is my first (and only, at least for this series) dive into a true “setting agnostic” game, not built for any one genre, but meant for games in any of them.

Cortex Prime

Truth be told, I didn’t know that Cortex Prime existed until recently. Instead, I knew Marvel Heroic Roleplaying, a 2012 game by Margaret Weiss Productions and by far my favorite (out of five!) TTRPGs made under the Marvel banner. Marvel Heroic Roleplaying received rave reviews and introduced several innovative mechanics well-suited to the superhero genre. Sadly, the company lost its Marvel license within a year of launching the game and thus disappeared as quickly as it appeared. My sense is that if Margaret Weiss had retained the license, MHR would be talked about today as much as FASERIP, and likely would have spawned Cortex Prime—a generic system using the same engine as MHR—sooner. Instead, designer Cam Banks took the guts of that original game to a 2017 Kickstarter, and Cortex Prime released three years later. It may have sat dimly in my awareness the past few years alongside systems like Genesys and Cypher, but I had mostly steered away from generic systems towards more specific and unique game experiences. At some point this year, I made the connection between Cortex Prime and Marvel Heroic Roleplaying, rubbed by eyes in disbelief, and promptly ordered the core rulebook.

The first thing to say about Cortex Prime is that it is beautifully produced. The cover, the interior art, the graphics used to explain game concepts, the layout… it’s all stunning. If the Supers! RED rulebook sits on one end of a sensory-stimulation spectrum, Cortex Prime is on the other.

It’s also a relatively unique rulebook in two ways: First, it reads like a “Game Design 101” textbook as much as a game instruction manual. Everything beyond the core mechanics in Cortex Prime is modular, and optional rules (called, in fact, “mods”) take up more room than the base rules, each painstakingly considered and guiding when you might use or not use that option. Because it’s a generic system, everything has a specific and technical term abstracted away from any one genre, and it’s a game that requires you to think beyond those technical terms to their application. Second, and relatedly, the book is targeted at Game Masters, not players. Because of its modular, design-the-game-to-your-world nature, Cam writes the book to bring GMs into the game design tent, letting them choose what sort of game they want to play. Cortex Prime is the single most earnest attempt I’ve seen to allow GMs to run the very specific game they want to play.

A number of great reviews of the system exist, and I’ll link to a few here by Mephit James, Gnome Stew, and Jeff’s Game Box. The best summary of the core mechanics are from a terrifically-written review by Cannibal Halfling, which I’ll quote here:

“Cortex is at its core a ‘roll and keep’ dice mechanic. For any challenge the player assembles a dice pool of around three dice, rolls them, and keeps the highest two results. Depending on which of your character’s traits are relevant to the roll, you could be rolling d4s, d6s, d8s, d10s, or d12s, with d6 being average, larger dice being better, and d4 being much less good, especially considering the high probability of rolling a 1. All dice rolls are opposed rolls; the base dice pool that the GM rolls is two dice whose size vary depending on the difficulty of the task.

There are two other mechanics which depend on the die results. First is the Effect Die. Once a player chooses the two dice they wish to keep, they choose the largest remaining die to be an Effect Die. The Effect Die determines the impact of certain dice rolls, and is dependent on the size (rather than result) of the chosen die. This does mean that it might sometimes be advantageous to choose a lower absolute result (provided it still meets the threshold for success) if it produces a larger Effect Die. Second result-based mechanic is the Hitch. A Hitch occurs when a player rolls a 1 on one of their dice. A die showing a one cannot be chosen for results or for the Effect Die. While there are no direct consequences beyond that for rolling a one (only rolling all 1s is considered a critical failure and is called a Botch), the GM may choose to spend that 1 on the roll to create a Complication. Complications, and their positive counterparts Assets, represent circumstances or items that exist in a scene, much like Aspects in Fate. A GM can add the die value of a relevant Complication to the dice pool that opposes a character’s roll, while the player can do the opposite with a relevant Asset. When a character creates an Asset, they may use the Effect Die to determine its die size and therefore its impact on the scene. The other core mechanic of note is the Plot Point System. Each player starts play with a Plot Point, and when the GM activates a Complication from a player rolling a 1, they also give that player a Plot Point. Plot Points can be spent on activating abilities, counting more dice in rolls, and preventing a character from being Taken Out of a Conflict. As more options are defined, so too are more ways to earn and spend Plot Points.”

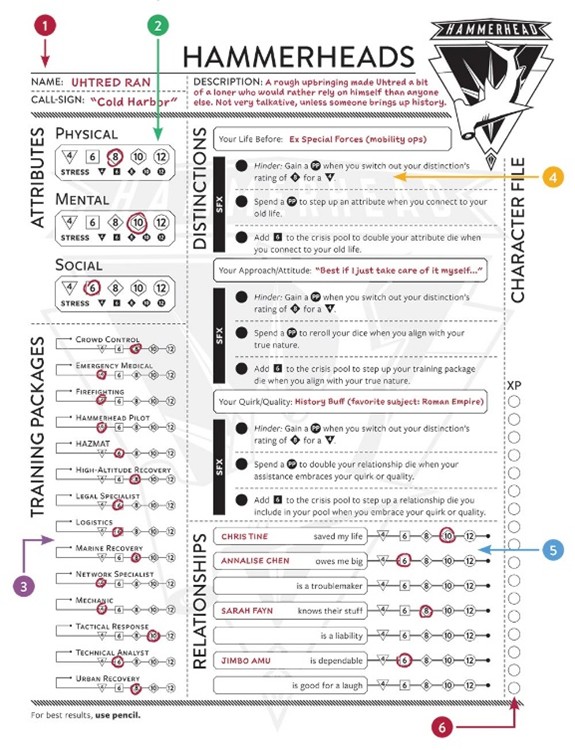

For the previous games, I made a sample character to test out the system. I can’t do that here, because to make a character in Cortex Prime means first making a dizzying number of choices about what mods exist in a particular world. Are we defining characters by Attributes, Skills, Roles, Powers, Relationships, Affiliations, Values, or something else? What do the superpowers do in this world? What factions exist that characters can join? Etcetera etcetera etcetera. Every character sheet in Cortex Prime is unique to that GM’s vision for the world. Take, for example, the same character sheet on the game’s website, for their sample Hammerheads (sci-fi) setting:

Everything on the sheet above—the three Attributes, the Training Packages, how Relationships work, what Distinctions matter—it’s all a setting-driven choice that the GM made before a player ever got involved. The possibilities are dizzying, and means that, once a GM has done the work of designing the world, everything in it bends towards the specific setting and stories in that setting.

Why Cortex Prme Works For Me

In a lot of ways, Cortex Prime is my wildest dream come true. It is a system designed for genre mashups, to allow GMs to feel unconstrained by any pre-existing setting. This is exactly what I’ve been searching for in this exploration. Reading through my criteria at the top of this post, it’s hard to see how any of the next game systems are ever going to address my criteria better than Cortex Prime. I get the strong sense that I could spend months worldbuilding and turning all the modular knobs to create exactly, EXACTLY what I want to do. Heck, once I’d done this work, I would have a game sourcebook in my hands that I could use far beyond my own solo play adventures. I would be tempted to consider writing adventures for my world and publishing them, surely reaching out to my regular game group to start a campaign. It’s kind of like a dream come true for homebrew worldbuilders.

What about jumps in character leveling, something that I’ve been using as a primary screen against other systems? You guessed it: There are mods for that too. Character advancement is its own section in the Cortex Prime rulebook, and I could make leveling up as milestone-driven or dramatic as I want.

Finally, once the world and game are built and all that knob-fiddling is done, the game has exactly the balance between crunch and narrative that I’ve been seeking. The mechanics are clear and easy to execute, and the decisions lead to exciting story moments. Even though the book often reads like a dense technical manual, it’s obvious that the density of mechanics is meant to allow the GM to make choices before players get involved, but that gameplay is meant to be fluid and fun. Look back to the game that launched the system in the first place, Marvel Heroic Roleplaying. In a lot of ways, MHR is an example of what Cortex Prime looks like once the GM choices are done.

The cherry on top: Because it’s a new game with such a wide scope and elegant presentation, the community around Cortex Prime is still vibrant. Unlike some other games I’m considering, I have no doubt that there would be plenty of people with which to bounce ideas or to lend inspiration. Moreover, I expect more and more setting books will be released over time, providing a whole ecosystem of Cortex Prime ideas to mine.

So, am I done? Did I find my perfect system? It sounds like it, right?

My Cortex Prime Hesitations

On average, I think each page of the ~250-page Cortex Prime rulebook took me more time to consume than any other game book I own. I had to reread sections multiple times to grok it and connect what I was learning with other sections, taking breaks between sections to allow my mind to breathe. It’s the only rpg book in memory that I’ve brought on an international business trip so that I could have the long plane rides to read it without distraction. To be clear: I’m not criticizing the book’s presentation or layout. For me, learning Cortex Prime is akin to learning a new language. Cam Banks has invited me to become a game designer and given me tools to do so. It’s as if I started the process of finding the perfect car for myself and stumbled upon a custom-kit dealership, where I can have any unique car I want if I’m willing to learn how to build it.

What I’ve come to realize, though, is that I’m not fundamentally a game designer. At best, I’m a competent GM who is comfortable homebrewing certain rules and tweaking settings to my taste. I’m a writer first, game player second. I don’t aspire to publish my own game system. Jumping back to my analogy, I’m a car enthusiast, not a mechanic—I want to buy a car and have someone give me the keys, complete with a maintenance plan if I run into trouble later. It’s clear to me that Cortex Prime offers the exact game experience I want for my project, as long as I’m willing to put in the significant work to assemble it from parts. Is that the work I want to do? I don’t think so. Everything about Cortex Prime feels tantalizingly full of possibilities but frustratingly far away.

I have two additional quibbles, but they are minor compared to the daunting, steep learning curve of building the system to my homebrewed world. First, as I’ve said throughout this series, Dungeon Crawl Classics titillated me with the story possibilities inherent in random tables. The more randomness I can insert into my process, the more that I surprise myself in my storytelling. Unless I want to build the tables myself, nothing about character creation in Cortex Prime is random. I’m sure that Cam Banks would encourage me to build those tables, but it’s just another step to a long process before I get to play and write. Woof.

Second, it sounds like there is some collective handwringing in the Cortex Prime community about how licensing works with the system (another article on this topic is here). In other words, once I’d put in the months of fiddling with the system to have it exactly represent my homebrewed, mashup setting, how public could I be with the choices I’d made? If I wanted to start releasing bits on this blog that became my own specific character sheets, powers lists, etc. – who owns those? It makes sense that there are legal questions there, because as I said, the Cortex Prime book feels uniquely like a game design toolbox more than a typical game rulebook. I don’t have specific goals or an endpoint in mind for this project (and honestly am not particularly ambitious about it), but I’d hate to regret choosing it as a system without fully educating myself on how licensing works. Add this step to the long lists of things I’d have to understand before beginning to play, which just all makes me want to sigh heavily.

One Game to Rule Them All

If it’s not obvious, I’m incredibly impressed by Cortex Prime as a system. It’s brilliant and unlike anything else I have on my TTRPG shelves. Kudos all around to Cam Banks and anyone else who created it.

It’s also a sobering game to explore. On the one hand, Cortex Prime delivers exactly what I want, as long as I’m willing to put in upfront work to create it. My resistance to doing that work is palpable, however, and makes me realize that I want a game that satisfies my requirements without needing to design the game myself. Back to my car analogy, I’d rather spend more time test-driving cars, finding the best one of the options available that I can drive right off the lot, than learning the skills necessary to build my own from a kit. There’s a reason that I spend time playing games and writing fiction and don’t spend that same time designing games. I hadn’t been forced to confront my missing game-designer gene until Cortex Prime.

As a result, I’ll keep it as an option, but distantly behind the others. If I truly can’t find something that works for me—or if I find myself with tons of free time and a willingness to crack my designer knuckles—it’s cool to know that Cortex Prime is there waiting for me.

Top Contender: ICONS

Second: Supers! RED

Third: Cortex Prime

Not currently in consideration:

Pingback: Choosing a Supers System, Part 4: ICONS – My Hero Brain